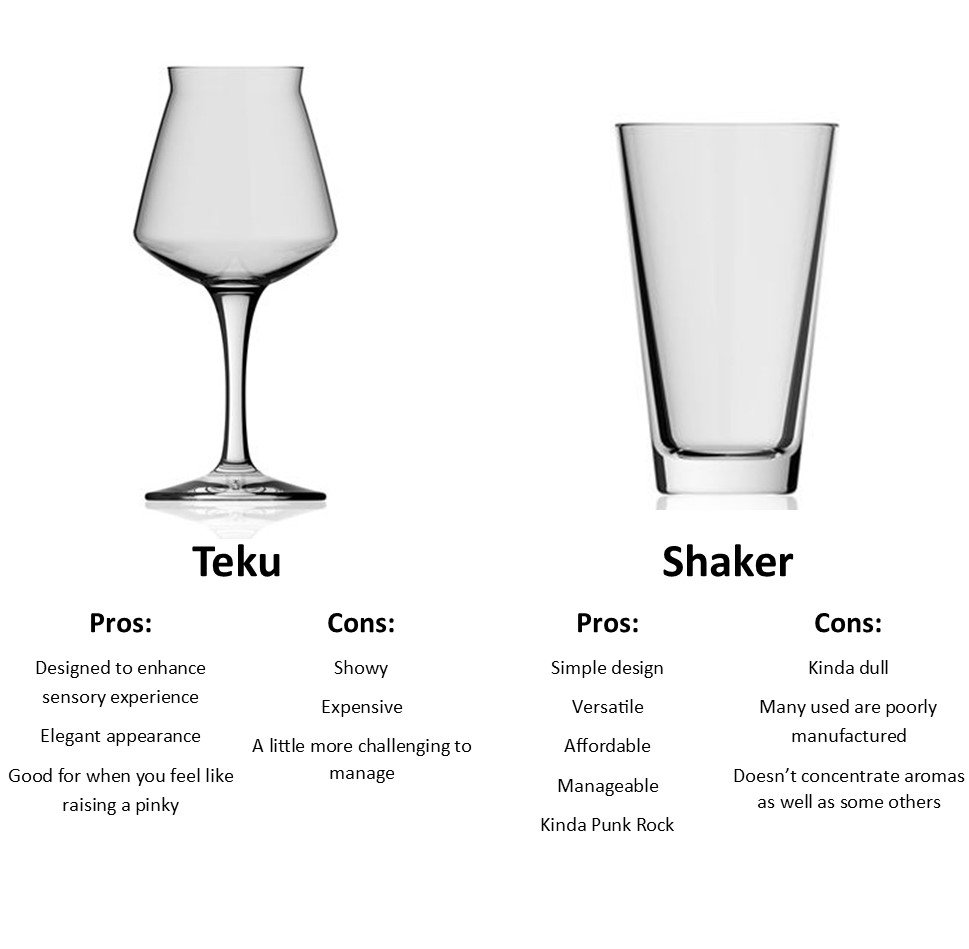

The shaker pint and the Teku are two of the most despised beer glasses, and besides both being glass vessels used for drinking, they have nearly nothing in common. One is an incredibly basic shape; a conical tumbler that has been around forever for all kinds of uses. The other is a modern creation. An angular, stemmed glass made specifically for beer.

Neither are worthy of much loathing (I mean, they’re just glasses, people), yet beer nerds have very strong opinions on them. I find them interesting as they are so different, and, at the same time, so debated in the contemporary beer world. (I think. Probably. Right? Is this just my perception? Probably the shaker more than the Teku.)

Shakers have been part of beer culture for much longer than Tekus. Some are better than others due to their manufacturing. Countless breweries in the United States have used them. Many breweries that sell/use more interesting glassware will still sell/use shaker pints.

The term “pints” is used loosely here. They can come in varying sizes, which is part of the reason some don’t care for it. The unpredictability of what a “pint” is when you order one. That’s a matter that is formally regulated in other beer-drinking cultures.

Do they add much to your drinking experience? No, not really. But do they really detract to the level that they deserve the hatred they receive? No, not really. Knocking others for using them is a little gatekeepy. I was probably like this at one point. I also shunned Nirvana when I was a kid because they were on a major label. I grew up. Shaker haters can too. They’re not that bad.

Some of the criticisms are that they lack features that elevate the drinking experience (aroma, e.g.) and that their thick composition creates issues with temperature. An argument is that the thicker glass retains the heat from one’s hand more so than thinner glass. This assumes people hold their beer the entire time they drink it and will cradle the beer long enough for this to become an issue.

Tekus were created in 2006 in Italy and are produced by the German glassware company Rastal. Technically, the name is spelled TeKu, representing the names of the two creators, Teo Musso and Lorenzo “Kuaska” Dabove. Musso is the brewer/owner of the Italian brewery Birra Baladin.

The websites for both Rastal and Baladin include fluffy language about how great the Teku glass is. It’s pretty. It has a modern look and works well if you like/want a stemmed glass. I like that it was specifically designed for beer and the way the curve at the top hugs the lip. Beyond that, I don’t think there are any major differences between it and most other stemmed beer/wine glasses with a decent bowl shape. This may be the reason why others gripe about it. Is it really necessary? The main complaint people seem to have about the Teku is its shape, which many people find a bit pompous, or simply unattactive.

Some of the content in this table might appear a little contradictory. But I suppose it’s possible that, for example, the Teku can be elegant and showy at the same time. Likewise, the shaker has a simple design that can be beneficial and dull at the same time. Yes, it’s basic, but sometimes basic is cool too. Tekus may help concentrate aroma, but if you have an already aromatic beer, you will still get a great sense of that if you hover your beak over a shaker.

This post is by no means a call for beer bars to start making use of either of these glasses. There are plenty of other options that are better suited for most. But if a beer bar were to use a shaker pint, it’s worthwhile to invest in a quality product. For example, Rastal makes Tekus, but they also offer a variety of shaker-style glasses that are high quality.

And just like all other glassware, once you’ve made the investment, you need to properly care for it even if it’s a shaker (i.e. no stacking, properly cleaning, etc.) Most importantly, as a customer, try not to let glassware style preferences get you bent out of shape when you’re served a beer. If you can put your feelings aside, there’s a pretty good chance you can still enjoy your beer no matter what the glass is. With all the challenges we face in life, glassware styles are something to enjoy and celebrate, but never something that should cause an uptick in our blood pressure. Except for those goddamn cheap UK-style dimple mugs everyone uses for lager.